Keeping tradition alive in the trade

By Dave Hunter

‘LOOKING after the trade’ was very much the philosophy of Raymond Miquel, the legendary boss of whisky company Arthur Bell & Sons in the 1970s and 80s.

Miquel, who led the company through a dramatic expansion period until its acquisition by Guinness in the mid-80s, was a stickler for professionalism and attention to detail in his company. And the people who worked for him were in no doubt about what was expected of them.

The famous ‘green blazer brigade’ – the Bell’s sales team named after the distinctive green blazers they would wear at industry events – were a common sight in Scottish pubs as well as industry events.

One of those salesmen, Bob Taylor – known these days as Uncle Bob – now speaks about his former boss with a mixture of fear and admiration, describing him variously as ‘deadly’ and ‘a wee dictator’, but always with respect for what Miquel achieved during his time at Bell’s.

Bob joined Bell’s in 1980 after having held sales positions for two brewers.

Arthur Bell & Sons was an enviable company to work for at the time. Its salespeople were salaried, rather than working on commission, and were supported by generous expense accounts. But they were expected to work for those privileges.

Each salesperson would have to make 20 visits to on-trade customers every day, in addition to hosting tasting events and trips.

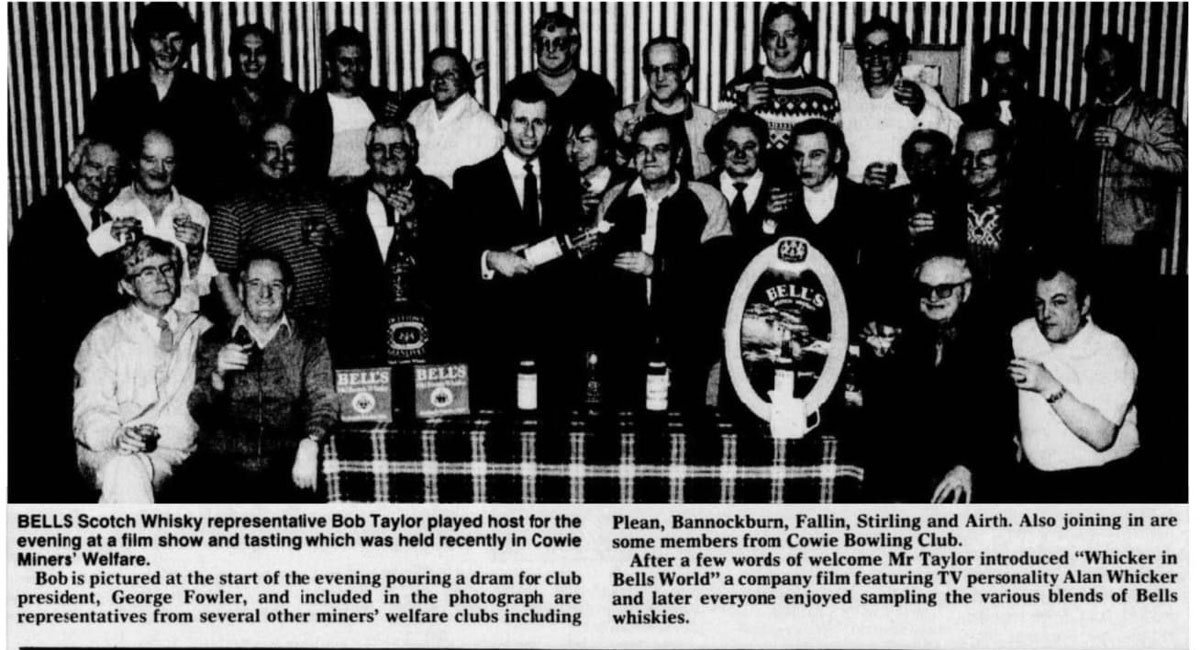

“As well as the job we had to do during the day we had to do whisky tastings where they showed a film with Alan Whicker,” Bob told SLTN.

“We’d get all the teams up from all the bars. Every licensee in the area. You poured the drinks for them and they had a great night. But they had to watch the film.”

On every call, a salesman was expected to buy regular customers a round of Bell’s. Money had to be kept in your pocket. Mr Miquel wouldn’t have his reps digging around in wallets for change. Wallets were mean. They weren’t up to the image the managing director wanted for his salesmen.

They were also expected to generate PR for the company by presenting pubs with bottles of Bell’s whisky and then sending pictures of the presentation into local papers.

On occasion – in Bob’s patch of the east end of Glasgow – this tradition could lead to trouble.

“I was presenting a decanter to a pub at Parkhead Cross,” he said.

“Drove up in the morning, about half past ten. Had a photographer with me. Every new licensee had to get a decanter presentation.

“You got a photo with the wife and then you took that photo to all the trade people and papers. It was free publicity. It was simple in those days.

“Anyway, I was in presenting the decanter. We got the photos, went to leave. The door’s locked. They’d locked us in and done my motor. We had to phone somebody to let us out.

“We went out and the boot was up and all the whisky was gone!”

Events, too, could be hard work.

Despite the convivial atmosphere, the Bell’s sales team weren’t in attendance for fun. These were work events. No two Bell’s team members were to sit together. The focus always had to be on the customers.

Reps took to carrying notebooks to record details about the licensees and staff in attendance. God help the rep who couldn’t introduce Mr Miquel to his valued customers.

A legendary workaholic, Miquel wouldn’t even relax on the golf course.

During one of the company’s golf days Bob was horrified to find himself paired with the managing director. But one of the other company salesmen was about to have a much worse time.

Bob recalled: “We come off the second hole. A ball hits the green. It was a par three. It rolls back to two feet. Miquel’s first words to me, quick as a flash: ‘Robert, who hit that shot?’ I said ‘it was (a salesman) from Newcastle, Mr Miquel’.

“He said ‘he’s playing too much golf’. One month later, sacked.”

Tipped off by the salesman’s suspiciously-strong golf game, Miquel had a manager look into the man’s call record. It wasn’t up to scratch and that was that.

But while he demanded high standards, there was a lot to like about Miquel’s approach to whisky and the licensed trade.

Under his leadership, Arthur Bell & Sons raised money for a number of industry organisations and charities, and Miquel’s attitude to whisky was ahead of its time.

When Bob asked the boss how people should be drinking their whisky, his answer was straightforward.

“You tell anybody that asks you that, Robert: drink it the way you like it. They want to put anything in it, that’s the way to drink it. Don’t you dictate to people how they drink their drink.”

And reps were under strict instructions to dance with older customers first at industry events and ceilidhs, rather than making a beeline for the attractive young barmaids. That wouldn’t do. No one was to be left out, on the orders of Mr Miquel.

Even decades later, the Bell’s approach to building brands continues to echo with Bob. After staying with the company after its takeover by Guinness – and the eventual transformation into Diageo – he set up his own agency and successfully launched a number of brands into the Scottish market, including Magners.

His latest project is a rum distilled in Dumbarton named Island Slice.

And Bob continues to pursue the same face-to-face, relationship-building approach that was employed at Bell’s all those years ago.

“When people worked for me I’d say your objective when you go into a call is that people remember you when you walk out the door,” said Bob.

“It doesn’t matter who you talk to.

“In the Diageo days the thing was ‘make an appointment to talk to the decision maker’.

“But see the wee lassie behind the bar? In six months she might be running the place. And in a lot of cases that’s happened to me. I get it all the time.

“Because people remember you. People like a laugh. That’s a hard job. Selling drink and working in pubs is a hard job. You’ve got to give them a bit of respect. Some people don’t give them respect. They treat them like servants. They treat them in the wrong way.

“They think because they’ve got a rep job that they’re better than publicans. They’re not better than them. The publicans are keeping them in a job.

“With Miquel, that was his way of working: you look after people.”